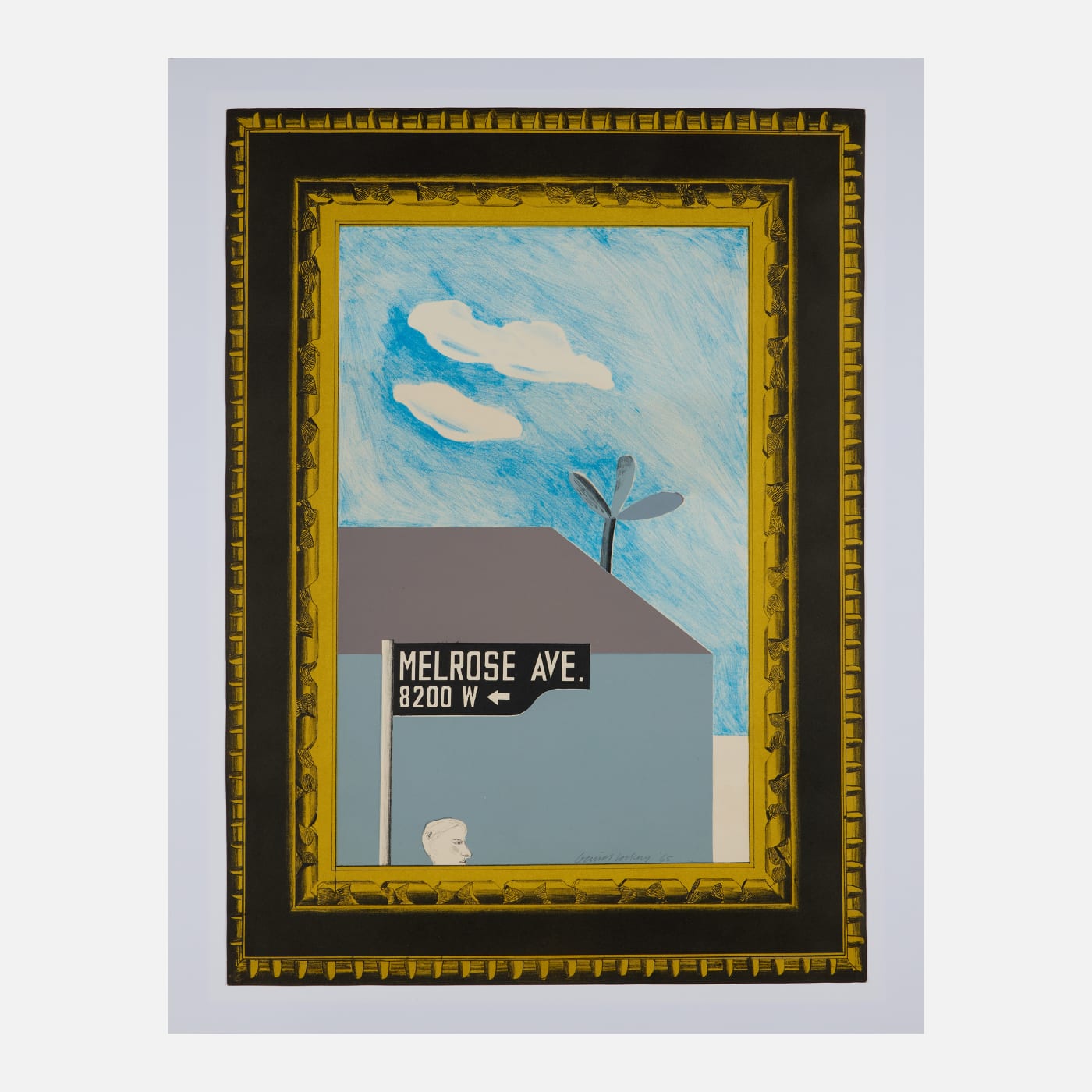

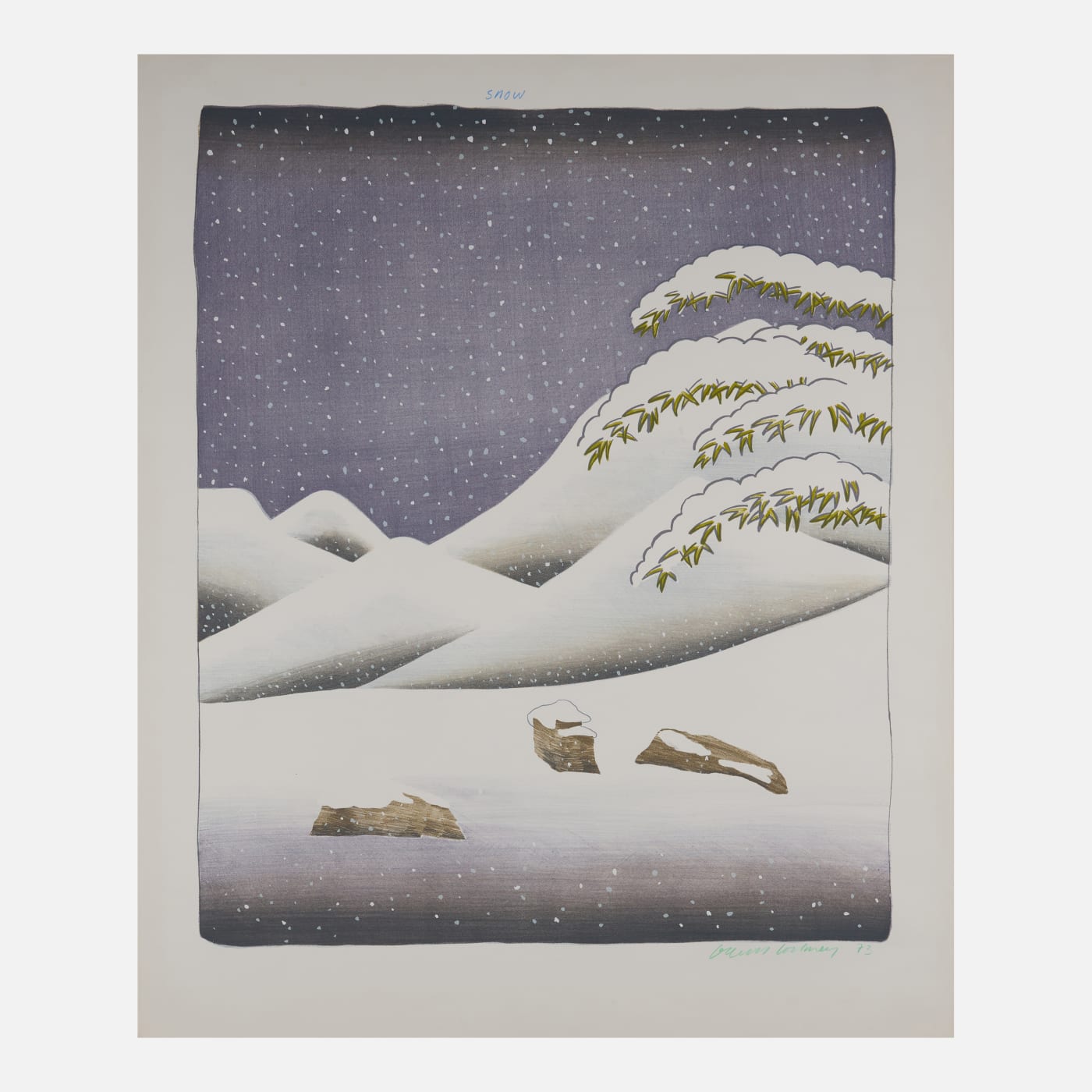

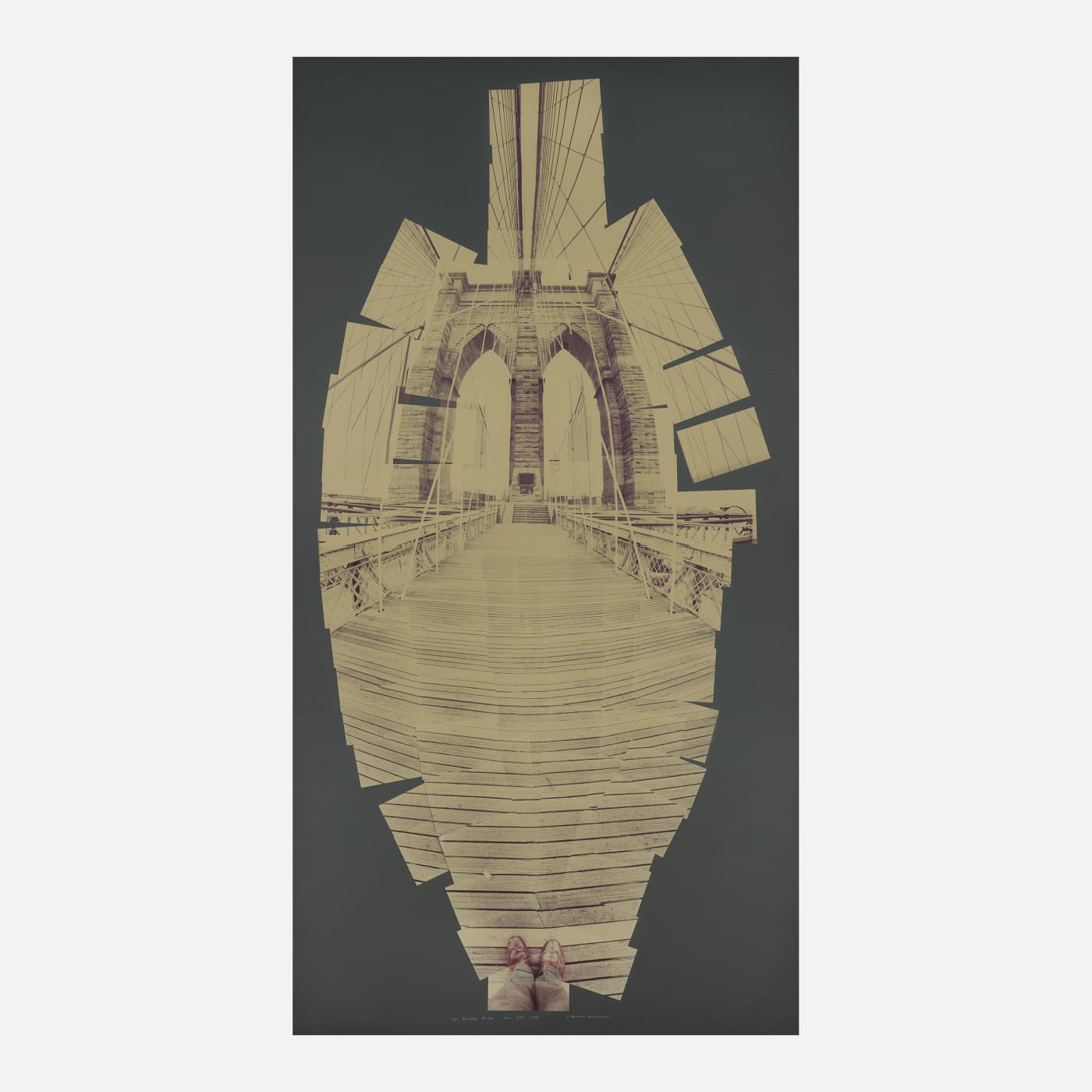

David Hockney's Alphabet

Hockney’s Alphabet is a diverse portfolio of works that draws together Hockney’s literary influence with his experiments in mark-making. Halcyon is pleased to present the portfolio at Living in Colour.

Here we have devised our own version of Hockney’s Alphabet ‘H to Y’ to explore the artist’s core themes, collections and inspirations.

If you are interested in adding to your collection speak to an art consultant today - info@halcyongallery.com

E is for Etching

While a student at Bradford Art School, Hockney began experimenting with different printing processes. Hockney is said to have learned the basic premise of etching in fifteen minutes via his then-classmate and friend, Ron Fuller. Harnessing his new skill, a flurry of works stem from this period of immense creativity, with Hockney finding an affinity with the medium and effortlessly adapting to its challenging properties. His earliest etchings are also testament to his broad frame of reference, with many prints referencing key art movements, like Cubism or Expressionism, advertising campaigns or even literary sources. Hockney is experimental with his etching practices, often mixing printing techniques to create his desired effects.

Etching is an intaglio (incising) printing process. The artist starts with a polished and blemish-free metal surface or plate (typically made from zinc, copper or iron). The plate is then coated with a wax or acid-resistant varnish; this layer is called the ‘ground’. From here, the artist uses a sharp tool to incise their desired image into the ‘ground’. Following this, the artist either douses, or plunges, their plate into an acid bath. The acid attacks the areas of the metal plate made visible by the incisions, eating away at the metal and creating deep grooves. The amount of time the plate is exposed to the acid determines the depth and width of the grooves. When the desired effect is reached, the artist removes the ‘ground’ layer with a solvent, revealing the now-incised metal plate. A layer of ink is carefully applied over this plate, ensuring that it penetrates each of the grooves. Once satisfied, the artist wipes the plate clean, leaving only the ink deposits in the grooves behind. Finally, the plate is covered with damp paper and several blankets that help cushion the plate, and it is fed through a heavy roller. This process transfers the ink from the grooves onto the paper.

Etching allowed Hockney to achieve very fine details, as seen in Two Vases in the Louvre (1974) where Hockney effectively emphasises depth and materiality. The window with a view to the courtyard and buildings beyond and the three-dimensionality of the two vases bookending the bay epitomise this.