David Hockney and Printmaking

David Hockney’s printmaking journey shows his constant curiosity and willingness to experiment, qualities that have shaped his entire career. From his early studies at Bradford School of Art to his use of new technologies in the 1980s, Hockney's approach to printmaking is as bold and innovative as his approach to painting.

If you are interested in adding to your collection speak to an art consultant today - info@halcyongallery.com

David Hockney’s journey into printmaking began at Bradford School of Art, where he was immersed in the teachings of traditional artist groups like the Euston Road School and influential modernists like Walter Sickert (1860-1942). Initially inspired to capture the essence of his hometown, the stark streets and muted colour palettes of Bradford soon disenchanted him. This disillusionment ignited a passion for experimentation, leading Hockney to explore the dynamic world of printmaking. His relentless curiosity, interrogation of techniques and insatiable drive to push the limits of the medium are hallmarks of his oeuvre. David Hockney’s works – both his paintings and his prints - are widely regarded and his ceaseless energy to bring to life even the simplest of forms is apparent.

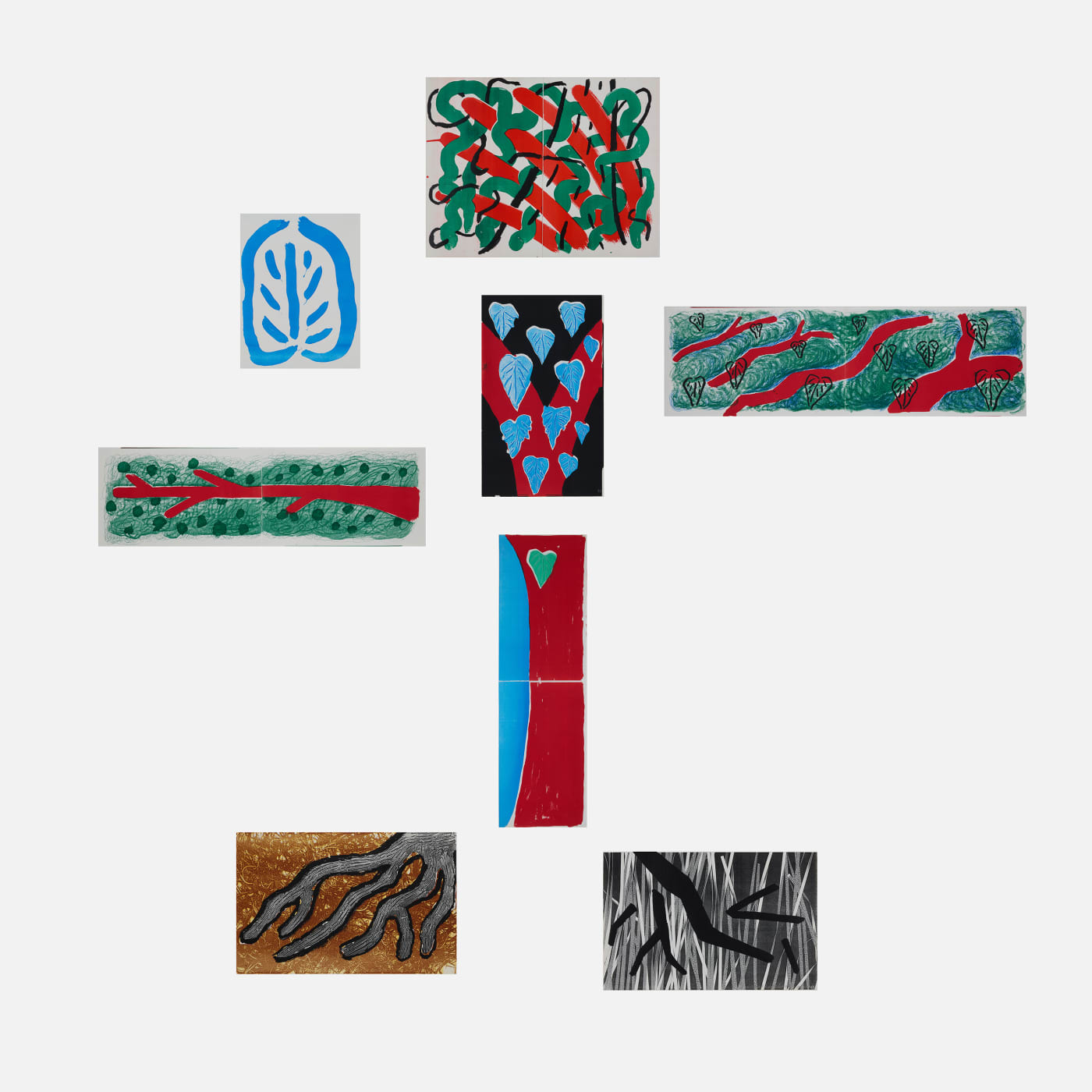

After Bradford, Hockney went on to study at the Royal College of Art (1959-1961). A prerequisite of the course was purchasing art supplies, and so it interested him when the prints department gave out free materials. With financial concerns alleviated, Hockney found creative freedom, drawing inspiration from fellow class-members as he navigated the bounds of this new medium. In his early years, he stuck to the two mainstream printing techniques: lithography and etching, and as he grew more advanced in his capacity to build composition and experiment with colour and line, he began diversifying his portfolio to include aquatinting and soft-ground and sugar-lift etching. By the 1980s, Hockney’s proficiency reached new heights as he imagined an entirely new printing technique that he coined his ‘Home Made Prints’. Devised using the everyday office-spec Xerox printer, these early prints are a nod to his growing digital proficiency that eventually gives way to his iPhone and iPad drawings of the 21st century.

Lithography

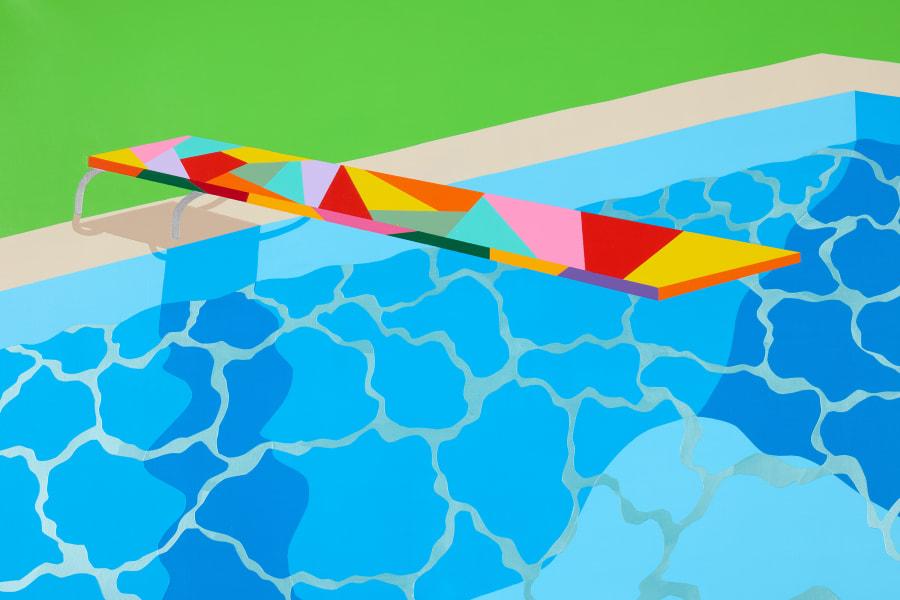

Lithography is one of Hockney’s primary printing techniques. His first documented prints, created in 1954: Self Portrait; Woman with a Sewing Machine and Fish and Chip Shop, demonstrate his early skill in capturing likeness and spatial depth, though few examples exist due to limited print-runs. Despite his early facility with this technique, there is a lull in his application of lithography for about a decade during which time his then-classmate, Ron Fuller, introduced him to etching. He returned fondly to lithography with his Hollywood Series in 1965, followed by a prolific period between 1970 and 1980, during which he produced many images of pools and seascapes. The Hollywood Series was created following his move to the United States. He wanted to create a complete series for any collector, six images that cover all subject bases: ‘It’s kind of a joke thing, a home-made art collection with bits of everything in it, a nude, an abstract, a landscape and so on.’ The natural ebbs and flows of his practice offer insight into Hockney’s interests and affinities at the time.

Lithography operates on the principle that oil and water repel each other. Artists draw directly onto a stone or metal surface with a greasy oil-based medium like wax or crayon. After the image has been drawn, the surface is treated with a chemical solution which transfers the image to the surface. The oily areas repel water and attract ink. A solvent is then used to remove most of the image – leaving a trace. The surface is wetted and inked – with the oily areas picking up the ink. Paper is placed over the top and rolled through a press, transferring the image. Due to the nature of the medium, multiple surfaces must be used if more than one colour is required.