Caravaggio to Griffiths

Mitch Griffiths’ work is rooted in the traditions of the Old Masters, showcasing an ultra-realistic style that calls to mind the great Renaissance painters like Titian, Michelangelo and Caravaggio. Like these masters, Griffiths’ paintings are characterised by a mastery of linear perspective, accurate anatomical representation, and vivid depictions of nature. However, it is not just technical accuracy that unites these painters; more significantly, it is the way that they each convey human emotion through evocative compositions.

If you are interested in adding to your collection speak to one of our art consultants today - email us at info@halcyongallery.com

Caravaggio’s work has long been admired by Griffiths, for both its technical brilliance but also its unflinching portrayal of the human figure in its raw, emotional complexity. Both artists approach their sitters with a realism that borders on the visceral, revealing vulnerability, intensity and sometimes, discomfort. Caravaggio was known for using models from his immediate surroundings – figures from streets, taverns or brothels of Rome. His characters were unidealised, sullied and presented with an unmistakable realism that set him apart from his Renaissance forebears. Figures like Fillide Melandroni and Mario Minniti reappear across Caravaggio’s works (Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1598, Martha and Mary Magdalene, 1598 and The Fortune Teller, 1595), embodying both the sacred and profane. For Caravaggio, these models were not just subjects, but conduits for deeper human experiences and social commentary. Griffiths similarly looks to interesting characters from different walks of life. He chooses models with striking features, from bright red hair to freckled faces and tattooed bodies. In each case, there is no emphasis on presenting idealised people, but instead accentuating real personalities and celebrating their idiosyncrasies.

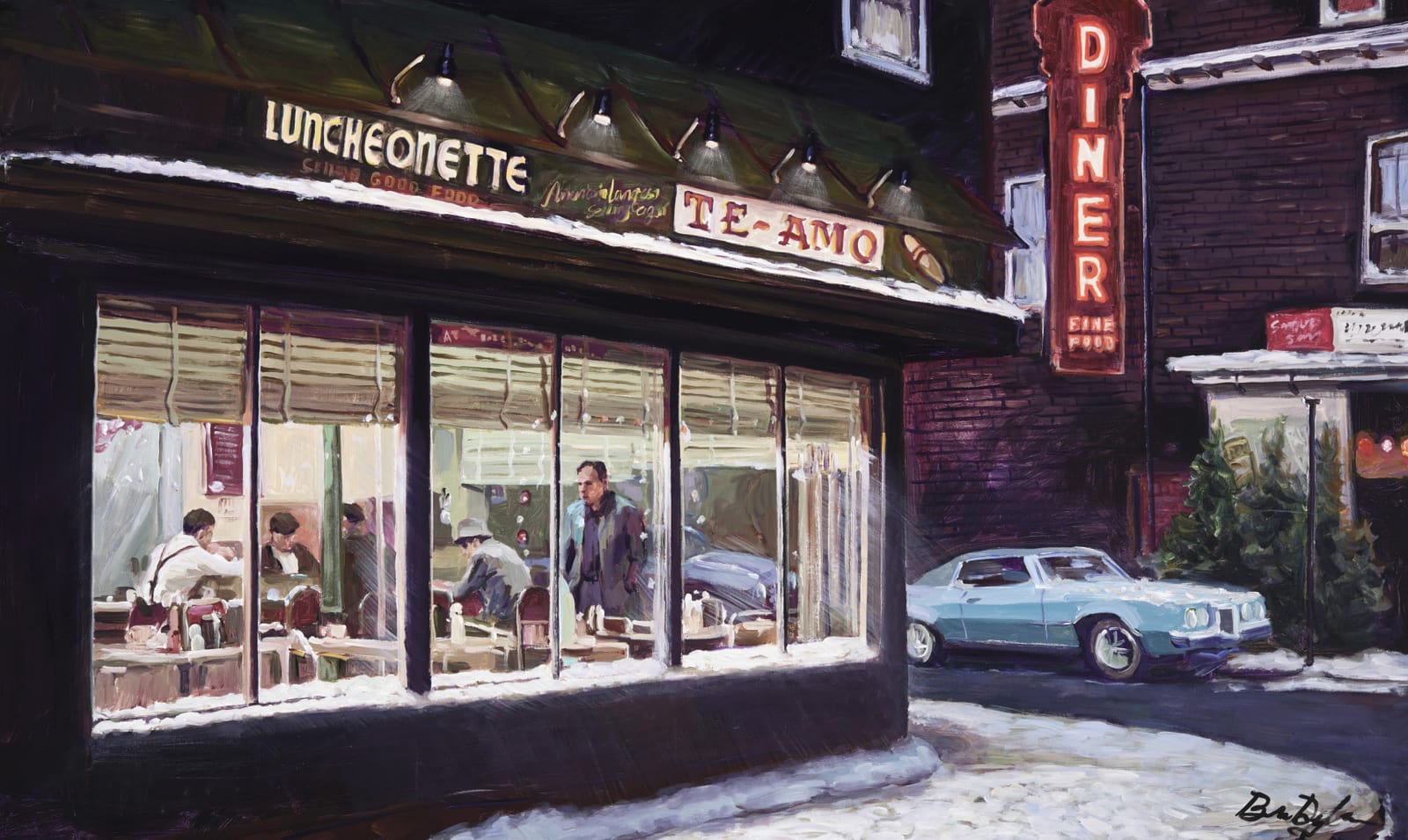

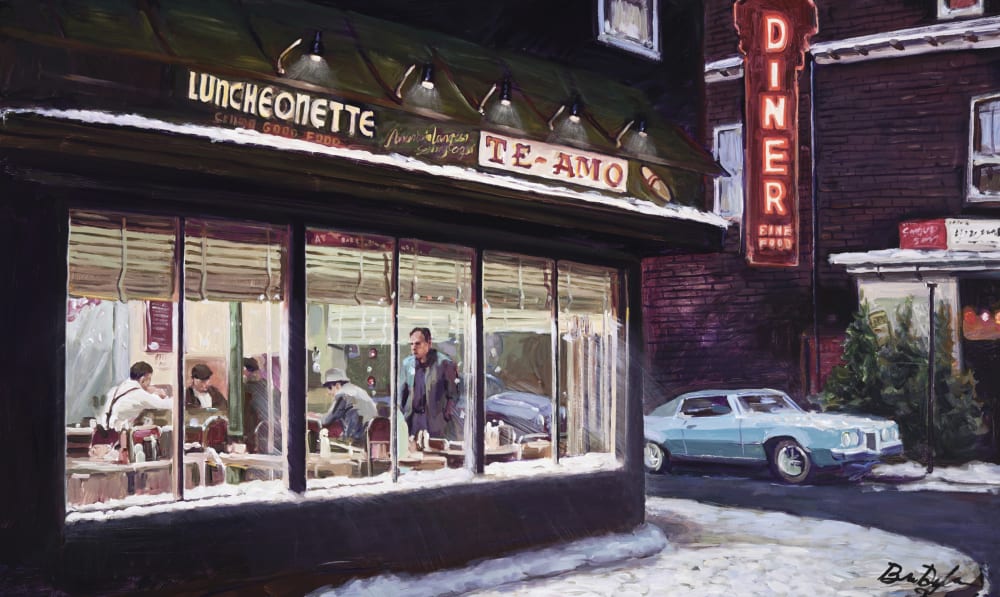

Just as Caravaggio’s choice of models grounded his work in real human experience, his use of chiaroscuro intensified this effect, adding another layer of psychological complexity. Caravaggio’s use of chiaroscuro is central to his practice. Sharp contrasts between light and dark dramatise his compositions. Faces emerge from the shadows as slivers of light break through the scenes. Warm, golden candlelight or fading daylight from a window bathes his figures, enhancing their presence. Yet, the darkness holds narrative and tension, reminding us of the more challenging, often sordid themes he chose to depict. In his works, musculature, furrowed brows, sooty feet, or bruised flesh become focal points in spotlit areas, their raw physicality heightened by the interplay of shadow and illumination. Light does not just reveal, but instead, traces the curves of skin as it folds over itself, capturing its vulnerability.

This manipulation of light, used to intensify the emotional charge of his subjects, is a technique Griffiths employs with striking effect. In his Unreel series (2024), chiaroscuro amplifies the psychological tension, drawing the viewer into the emotional depths of his sitters.