Pedro Paricio: Popularising Greek Mythology

Halcyon’s present exhibition, Sacred & Profane, engages with various mythological themes. The artists in the exhibition who choose to inform their paintings with mythological references are, inadvertently or not, interrogating the historic notion that art’s primary function has been religious in nature.

In the show’s exploration of paintings and sculptures as focal points of devotion, Pedro Paricio’s Narcissus, Venus and Flora (all 2024) stand alongside Mitch Griffiths’ works of intense realism, which secularise sacred subjects in a style reminiscent of the great Italian masters. Paricio, however, directly engages with myth by overtly titling his work after Greek gods, exploring both Renaissance and Surrealist narratives in the process.

View works by Pedro Paricio at 148 New Bond Street today and if you are interested in adding to your collection, speak to one of our art consultants now - email us at info@halcyongallery.com

The Myth of Narcissus

Pictorial adaptations of the beautiful hunter Narcissus have endured throughout art history. Some of the earliest known depictions were recently found in Pompeii, with frescoes uncovered in the atrium of a large house on Valentine’s Day in 2019. These vibrant frescoes, preserved under Mount Vesuvius’ volcanic ash since 79 AD., depict a regal and muscly Narcissus gazing at his own reflection in the water beneath his feet. Though the story’s origins lie in Greek mythology, it was the Roman poet Ovid who penned the most well-known version of the tale in 8 AD in Book III of Metamorphoses, reinforcing its presence in Italian visual culture.

The myth tells of Narcissus, a stunningly beautiful youth who rejected all suitors, including Echo, a nymph cursed to only repeat others' words. After a heartbreaking encounter, Echo faded away in sorrow, leaving only her voice behind. Narcissus’ cruelty and vanity angered the gods, and Nemesis punished him by making him fall in love with his own reflection. Unable to look away, he wasted away, leaving behind only a six-leafed white flower that now bears his name.

The tale of Narcissus warns of the dangers of obsession and the importance of remaining humble. The story, codified in morality, has been adopted many times by artists over the years.

Caravaggio’s Narcissus

Dalí’s Metamorphosis of Narcissus: Surrealism and Deception

Dalí’s 1937 Metamorphosis of Narcissus embodies the principles of Surrealism, its experimental visual language, dream logic and deep engagement with Freudian psychoanalysis. The painting employs trompe-l’oeil, an optical illusion technique that tricks the viewer into perceiving depth and three-dimensionality.

Dalí’s hyper-realistic landscape creates an uncanny dreamscape. On the left, Narcissus is depicted in a familiar pose, an unclothed man, his head resting on his bent knee, fingers trailing in the mirrored lake. But at the centre of the canvas, the magic of deception begins, the rock formations form a stark edge, splitting the scene in two. On the right, the composition repeats itself, but this time the figure of Narcissus has transformed. His body is now a bony hand, grasping an egg from which a delicate six-leaf flower blooms, a visual metaphor for rebirth and direct reference to Ovid’s tale. Dalí’s use of double imagery forces the viewer to question perception itself, while other details, such as a chessboard in the lower right, reinforce themes of fate and illusion.

Pedro Paricio’s Narcissus

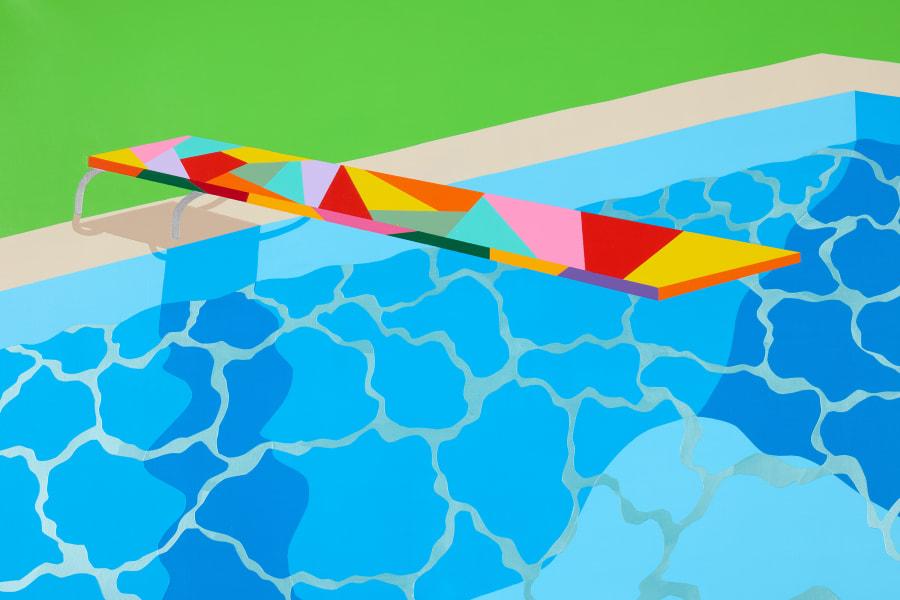

Pedro Paricio’s Narcissus (2024) directly appropriates and adapts Caravaggio’s version, but through a distinctly modern lens. He retains the structure of the original composition, yet his treatment of form is entirely his own. His flattened planes of colour, vibrant hues and kaleidoscopic shapes transform the work into something both contemporary and timeless.

Paricio’s use of Surrealist techniques, possibly including decalcomania or grattage (methods of spontaneous, mirrored image-making) in the reflection of the water beneath, enhances the sense of visual play. His Narcissus, rather than being rendered with Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro, is instead fractured, his head and arms dissolving into fragmented, geometric colour fields. The removal of any discernible background forces the viewer to focus solely on the figure before them.

In many ways, Narcissus is a self-referential work, not just in its direct connection to the myth, but in its engagement with the act of seeing itself. Just as Narcissus gazes upon his own reflection, so too does the viewer see themselves in Paricio’s shattered mirror. There is also reason to suspect that this work is a self-portrait, encouraging the viewer to correlate the myth with the artist and making the work an interrogation of self-reflection. As is true of most of Paricio’s works, his characteristic kaleidoscopic shapes invite the viewer to reconsider themselves in the narrative, in this case to the myth that continues to shape our understanding of human identity.